The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world’s largest Baptist denomination, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, and the second-largest Christian denomination in the United States, smaller only than the Roman Catholic Church according to self-reported membership statistics.

The word Southern in Southern Baptist Convention stems from it having been organized in 1845 at Augusta, Georgia, by Baptists in the Southern United States who split with northern Baptists over the issue of slavery, with Southern Baptists strongly opposed to its abolition. After the American Civil War, another split occurred when most freedmen set up independent black congregations, regional associations, and state and national conventions, such as the National Baptist Convention, which became the second-largest Baptist convention by the end of the 19th century.

The word Southern in Southern Baptist Convention stems from it having been organized in 1845 at Augusta, Georgia, by Baptists in the Southern United States who split with northern Baptists over the issue of slavery, with Southern Baptists strongly opposed to its abolition. After the American Civil War, another split occurred when most freedmen set up independent black congregations, regional associations, and state and national conventions, such as the National Baptist Convention, which became the second-largest Baptist convention by the end of the 19th century.

Since the 1940s, the Southern Baptist Convention has shifted from some of its regional and historical identification. Especially since the late 20th century, the SBC has sought new members among minority groups and to become much more diverse. In addition, while still heavily concentrated in the Southern United States, the Southern Baptist Convention has member churches across the United States and 41 affiliated state conventions. Southern Baptist churches are evangelical in doctrine and practice. As they emphasize the significance of the individual conversion experience, which is affirmed by the person having complete immersion in water for a believer’s baptism, they reject the practice of infant baptism. Other specific beliefs based on biblical interpretation can vary somewhat due to their congregational polity, which allows local autonomy.

The average weekly attendance was 5,297,788 in 2018.

Baptists in the British colonies

Most early Baptists in the British colonies came from England in the 17th century, after the established Church of England persecuted them for their dissenting religious views. The oldest Baptist church in the South, First Baptist Church of Charleston, South Carolina, was organized in 1682 under the leadership of William Screven. A Baptist church was formed in Virginia in 1715 through the preaching of Robert Norden and another in North Carolina in 1727 through the ministry of Paul Palmer.

The Baptists adhered to a congregationalist polity and operated independently of the state-established Anglican churches in the South, at a time when non-Anglicans were prohibited from holding political office. By 1740, about eight Baptist churches existed in the colonies of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, with an estimated 300 to 400 members. New members, both black and white, were converted chiefly by Baptist preachers who traveled throughout the South during the 18th and 19th centuries, in the eras of the First Great Awakening and Second Great Awakening.

Baptists welcomed African Americans, both slave and free, allowing them to have more active roles in ministry than did other denominations by licensing them as preachers, and in some cases, allowing them to be treated as equals to white members. As a result, black congregations and churches were founded in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia before the American Revolution. Some black congregations kept their independence even after whites tried to exercise more authority after the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831.

The Common Man’s Equality

Before the Revolution, Baptist and Methodist evangelicals in the South had promoted the view of the common man’s equality before God, which embraced slaves and free blacks. They challenged the hierarchies of class and race and urged planters to abolish slavery. They welcomed slaves as Baptists and accepted them as preachers.

Isaac (1974) analyzes the rise of the Baptist Church in Virginia, with emphasis on evangelicalism and social life. A sharp division existed between the austerity of the plain-living Baptists, attracted initially from yeomen and common planters, and the opulence of the Anglican planters, the slave-holding elite who controlled local and colonial government in what had become a slave society by the late 18th century. The gentry interpreted Baptist church discipline as political radicalism, but it served to ameliorate disorder. The Baptists intensely monitored each other’s moral conduct, watching especially for sexual transgressions, cursing, and excessive drinking; they expelled members who would not reform.

Isaac (1974) analyzes the rise of the Baptist Church in Virginia, with emphasis on evangelicalism and social life. A sharp division existed between the austerity of the plain-living Baptists, attracted initially from yeomen and common planters, and the opulence of the Anglican planters, the slave-holding elite who controlled local and colonial government in what had become a slave society by the late 18th century. The gentry interpreted Baptist church discipline as political radicalism, but it served to ameliorate disorder. The Baptists intensely monitored each other’s moral conduct, watching especially for sexual transgressions, cursing, and excessive drinking; they expelled members who would not reform.

In Virginia and in most southern colonies before the Revolution, the Church of England was the established church and supported by general taxes, as it was in England. It opposed the rapid spread of Baptists in the South. Particularly in Virginia, many Baptist preachers were prosecuted for “disturbing the peace” by preaching without licenses from the Anglican church. Both Patrick Henry and the young attorney James Madison defended Baptist preachers prior to the American Revolution in cases considered significant to the history of religious freedom. In 1779, Thomas Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, enacted in 1786 by the Virginia General Assembly. Madison later applied his own ideas and those of the Virginia document related to religious freedom during the Constitutional Convention, when he ensured that they were incorporated into the national constitution.

The struggle for religious toleration erupted and was played out during the American Revolution, as the Baptists worked to disestablish the Anglican church in the South. Beeman (1978) explores the conflict in one Virginia locality, showing that as its population became more dense, the county court and the Anglican Church were able to increase their authority. The Baptists protested vigorously; the resulting social disorder resulted chiefly from the ruling gentry’s disregard for public need. The vitality of the religious opposition made the conflict between ‘evangelical’ and ‘gentry’ styles a bitter one. Kroll-Smith (1984) suggests that the strength of the evangelical movement’s organization determined its ability to mobilize power outside the conventional authority structure.

The struggle for religious toleration erupted and was played out during the American Revolution, as the Baptists worked to disestablish the Anglican church in the South. Beeman (1978) explores the conflict in one Virginia locality, showing that as its population became more dense, the county court and the Anglican Church were able to increase their authority. The Baptists protested vigorously; the resulting social disorder resulted chiefly from the ruling gentry’s disregard for public need. The vitality of the religious opposition made the conflict between ‘evangelical’ and ‘gentry’ styles a bitter one. Kroll-Smith (1984) suggests that the strength of the evangelical movement’s organization determined its ability to mobilize power outside the conventional authority structure.

The First National Baptist Denomination in the United States

In 1814, leaders such as Luther Rice were able to help Baptists unify nationally under what became known informally as the Triennial Convention (because it met every three years) based in Philadelphia. It allowed them to join their resources to support missions abroad. The Home Mission Society, affiliated with the Triennial Convention, was established in 1832 to support missions in frontier territories of the United States. By the mid-19th century, numerous social, cultural, economic, and political differences existed among business owners of the North, farmers of the West, and planters of the South. The most divisive conflict was primarily over the issue of slavery and secondarily over missions.

In 1814, leaders such as Luther Rice were able to help Baptists unify nationally under what became known informally as the Triennial Convention (because it met every three years) based in Philadelphia. It allowed them to join their resources to support missions abroad. The Home Mission Society, affiliated with the Triennial Convention, was established in 1832 to support missions in frontier territories of the United States. By the mid-19th century, numerous social, cultural, economic, and political differences existed among business owners of the North, farmers of the West, and planters of the South. The most divisive conflict was primarily over the issue of slavery and secondarily over missions.

Critical Moral Issue Dividing Baptists

Slavery in the 19th century became the most critical moral issue dividing Baptists in the United States. Struggling to gain a foothold in the South, after the American Revolution, the next generation of Southern Baptist preachers accommodated themselves to the leadership of Southern society. Rather than challenging the gentry on slavery and urging manumission (as did the Quakers and Methodists), they began to interpret the Bible as supporting the practice of slavery and encouraged good paternalistic practices by slaveholders. They preached to slaves to accept their places and obey their masters. In the two decades after the Revolution during the Second Great Awakening, Baptist preachers abandoned their pleas that slaves be manumitted.

Slavery in the 19th century became the most critical moral issue dividing Baptists in the United States. Struggling to gain a foothold in the South, after the American Revolution, the next generation of Southern Baptist preachers accommodated themselves to the leadership of Southern society. Rather than challenging the gentry on slavery and urging manumission (as did the Quakers and Methodists), they began to interpret the Bible as supporting the practice of slavery and encouraged good paternalistic practices by slaveholders. They preached to slaves to accept their places and obey their masters. In the two decades after the Revolution during the Second Great Awakening, Baptist preachers abandoned their pleas that slaves be manumitted.

After first attracting yeomen farmers and common planters, in the 19th century, the Baptists began to attract major planters among the elite. While the Baptists welcomed slaves and free blacks as members, whites controlled leadership of the churches, their preaching supported slavery, and blacks were usually segregated in seating.

Black congregations were sometimes the largest of their regions. For instance, by 1821, Gillfield Baptist in Petersburg, Virginia, had the largest congregation within the Portsmouth Association. At 441 members, it was more than twice as large as the next ranking church. Before the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831, Gillfield had a black preacher. Afterward, the state legislature insisted that black congregations be overseen by white men. Gillfield could not call a black preacher until after the American Civil War and emancipation. After Turner’s slave rebellion, whites worked to exert more control over black congregations and passed laws requiring white ministers to lead or be present at religious meetings (many slaves evaded these restrictions).

Black congregations were sometimes the largest of their regions. For instance, by 1821, Gillfield Baptist in Petersburg, Virginia, had the largest congregation within the Portsmouth Association. At 441 members, it was more than twice as large as the next ranking church. Before the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831, Gillfield had a black preacher. Afterward, the state legislature insisted that black congregations be overseen by white men. Gillfield could not call a black preacher until after the American Civil War and emancipation. After Turner’s slave rebellion, whites worked to exert more control over black congregations and passed laws requiring white ministers to lead or be present at religious meetings (many slaves evaded these restrictions).

In addition, from the early decades of the 19th century, many Baptist preachers in the South argued in favor of preserving the right of ministers to be slaveholders (which they had earlier prohibited), a class that included prominent Baptist Southerners and planters.

The Triennial Convention and the Home Mission Society adopted a kind of neutrality concerning slavery, neither condoning nor condemning it. During the “Georgia Test Case” of 1844, the Georgia State Convention proposed that the slaveholder Elder James E. Reeve be appointed as a missionary. The Foreign Mission Board refused to approve his appointment, recognizing the case as a challenge and not wanting to overturn their policy of neutrality on the slavery issue. They stated that slavery should not be introduced as a factor into deliberations about missionary appointments.

In 1844, Basil Manly Sr., president of the University of Alabama, a prominent preacher and a major planter who owned 40 slaves, drafted the “Alabama Resolutions” and presented them to the Triennial Convention. These included the demand that slaveholders be eligible for denominational offices to which the Southern associations contributed financially. These resolutions failed to be adopted. Georgia Baptists decided to test the claimed neutrality by recommending a slaveholder to the Home Mission Society as a missionary. The Home Mission Society’s board refused to appoint him, noting that missionaries were not allowed to take servants with them (so he clearly could not take slaves) and that they would not make a decision that appeared to endorse slavery. Southern Baptists considered this an infringement of their right to determine their own candidates. From the Southern perspective, the Northern position that “slave-holding brethren were less than followers of Jesus” effectively obliged slave-holding Southerners to leave the fellowship.

A Proportionate Number of Missionaries

A secondary issue that disturbed the Southerners was the perception that the American Baptist Home Mission Society did not appoint a proportionate number of missionaries to the southern region of the United States. This was likely a result of the society’s not appointing slave owners as missionaries. Baptists in the North preferred a loosely structured society composed of individuals who paid annual dues, with each society usually focused on a single ministry.

A secondary issue that disturbed the Southerners was the perception that the American Baptist Home Mission Society did not appoint a proportionate number of missionaries to the southern region of the United States. This was likely a result of the society’s not appointing slave owners as missionaries. Baptists in the North preferred a loosely structured society composed of individuals who paid annual dues, with each society usually focused on a single ministry.

Baptists in Southern churches preferred a more centralized organization of congregations composed of churches patterned after their associations, with a variety of ministries brought under the direction of one denominational organization. The increasing tensions and the discontent of Baptists from the South regarding national criticism of slavery and issues over missions led to their withdrawal from the national Baptist organizations.

Baptists in Southern churches preferred a more centralized organization of congregations composed of churches patterned after their associations, with a variety of ministries brought under the direction of one denominational organization. The increasing tensions and the discontent of Baptists from the South regarding national criticism of slavery and issues over missions led to their withdrawal from the national Baptist organizations.

The Southern Baptists met at the First Baptist Church of Augusta in May 1845. At this meeting, they created a new convention, naming it the Southern Baptist Convention. They elected William Bullein Johnson (1782–1862) as the new convention’s first president. He had served as president of the Triennial Convention in 1841.

The Black church

African Americans had gathered in their own churches early on, in 1774 in Petersburg, Virginia, and in Savannah, Georgia, in 1788. Some were established after 1800 on the frontier, such as the First African Baptist Church of Lexington, Kentucky. In 1824, it was accepted by the Elkhorn Association of Kentucky, which was white-dominated. By 1850, First African had 1,820 members, the largest of any Baptist church in the state, black or white. In 1861, it had 2,223 members.

African Americans had gathered in their own churches early on, in 1774 in Petersburg, Virginia, and in Savannah, Georgia, in 1788. Some were established after 1800 on the frontier, such as the First African Baptist Church of Lexington, Kentucky. In 1824, it was accepted by the Elkhorn Association of Kentucky, which was white-dominated. By 1850, First African had 1,820 members, the largest of any Baptist church in the state, black or white. In 1861, it had 2,223 members.

Generally, whites in the South required that black churches have white ministers and trustees. In churches with mixed congregations, blacks were made to sit in segregated seating, often a balcony. White preaching often emphasized Biblical stipulations that slaves should accept their places and try to behave well toward their masters.

After the Civil War and emancipation, blacks wanted to practice Christianity independently of white supervision. They had interpreted the Bible as offering hope for deliverance, and saw their own exodus out of slavery as comparable to the Exodus, and abolitionist John Brown as their Moses. They quickly left white-dominated churches and associations and set up separate state Baptist conventions. In 1866, black Baptists of the South and West combined to form the Consolidated American Baptist Convention. In 1895, they merged three national conventions to create the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc.. With eight million members, it is today the largest African-American religious organization and is second in size to the Southern Baptist Convention.

Free blacks in the North had founded churches and denominations in the early 19th century that were independent of white-dominated organizations. In the Reconstruction Era, missionaries both black and white from several northern denominations worked in the South; they quickly attracted tens and hundreds of thousands of new members from among the millions of freedmen. The African Methodist Episcopal Church attracted the most new members of any denomination. White Southern Baptist churches lost black members to the new denominations, as well as to independent congregations organized by freedmen.

Free blacks in the North had founded churches and denominations in the early 19th century that were independent of white-dominated organizations. In the Reconstruction Era, missionaries both black and white from several northern denominations worked in the South; they quickly attracted tens and hundreds of thousands of new members from among the millions of freedmen. The African Methodist Episcopal Church attracted the most new members of any denomination. White Southern Baptist churches lost black members to the new denominations, as well as to independent congregations organized by freedmen.

During the Civil Rights Movement, most Southern Baptist pastors and most members of their congregations rejected racial integration and accepted white supremacy, further alienating African Americans. According to historian and former Southern Baptist Wayne Flynt, “The [Southern Baptist] church was the last bastion of segregation.

Major Internal Controversy

During its history, the Southern Baptist Convention has had several periods of major internal controversy.

Landmark controversy

In the 1850s–1860s, a group of young activists called for a return to certain early practices, or what they called Landmarkism. Other leaders disagreed with their assertions, and the Baptist congregations became split on the issues. Eventually, the disagreements led to the formation of Gospel Missions and the American Baptist Association (1924), as well as many unaffiliated independent churches. One historian called the related James Robinson Graves—Robert Boyte Crawford Howell controversy (1858–60) the greatest to affect the denomination before that of the late 20th century involving the fundamentalist-moderate break.

In the 1850s–1860s, a group of young activists called for a return to certain early practices, or what they called Landmarkism. Other leaders disagreed with their assertions, and the Baptist congregations became split on the issues. Eventually, the disagreements led to the formation of Gospel Missions and the American Baptist Association (1924), as well as many unaffiliated independent churches. One historian called the related James Robinson Graves—Robert Boyte Crawford Howell controversy (1858–60) the greatest to affect the denomination before that of the late 20th century involving the fundamentalist-moderate break.

Whitsitt controversy

In the Whitsitt controversy of 1896–99, William H. Whitsitt, a professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, suggested that, contrary to earlier thought, English Baptists did not begin to baptize by immersion until 1641, when some Anabaptists, as they were then called, began to practice immersion. This overturned the idea of immersion as the practice of the earliest Baptists as some of the Landmarkists contended.

Moderates–Conservatives controversy

The Southern Baptist Convention conservative resurgence (c. 1970–2000) was an intense struggle for control of the SBC’s resources and ideological direction. The major internal disagreement captured national attention. Its initiators called it a “Conservative Resurgence”, while its detractors have labeled it a “Fundamentalist Takeover”.

The Southern Baptist Convention conservative resurgence (c. 1970–2000) was an intense struggle for control of the SBC’s resources and ideological direction. The major internal disagreement captured national attention. Its initiators called it a “Conservative Resurgence”, while its detractors have labeled it a “Fundamentalist Takeover”.

Russell H. Dilday, president of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary from 1978 to 1994, described the resurgence as having fragmented Southern Baptist fellowship and as being “far more serious than [a controversy]”. Dilday described it as being “a self-destructive, contentious, one-sided feud that at times took on combative characteristics”.

Since 1979, Southern Baptists had become polarized into two major groups: moderates and conservatives. Reflecting the conservative majority votes of delegates at the 1979 annual meeting of the SBC, the new national organization officers replaced all leaders of Southern Baptist agencies with presumably more conservative people (often dubbed “fundamentalist” by dissenters).

Among historical elements illustrating this trend, the organization’s position on abortion rights within a decade had shifted radically from a pro-abortion position to a strong pro-life one, as in 1971, (two years before Roe v. Wade), the SBC passed a resolution supporting abortion, not only in cases of rape or incest—positions which even some Southern Baptist conservatives would support—but also as “clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother”—positions not supported by the conservative wing.

Among historical elements illustrating this trend, the organization’s position on abortion rights within a decade had shifted radically from a pro-abortion position to a strong pro-life one, as in 1971, (two years before Roe v. Wade), the SBC passed a resolution supporting abortion, not only in cases of rape or incest—positions which even some Southern Baptist conservatives would support—but also as “clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother”—positions not supported by the conservative wing.

Also, in 1974, (the year after Roe v. Wade) the SBC passed another resolution affirming its previous 1971 resolution, saying that it “dealt responsibly from a Christian perspective with complexities of abortion problems in contemporary society” while also in the same resolution claiming that the SBC “historically held a high view of the sanctity of human life”.

However, once the conservatives won their first election in 1980, they passed a resolution which completely reversed their prior positions on abortion, condemning it in all cases except to save the life of the mother. As such, all subsequent resolutions on the issue have followed the 1980 trend of being strongly against abortion and have gone further into opposing similar issues such as fetal tissue experimentation, RU-486, and taxpayer funding of abortions in general and Planned Parenthood in particular.

Renouncing Racist Roots

In 1995, the convention voted to adopt a resolution in which it renounced its racist roots and apologized for its past defense of slavery, segregation, and white supremacy. This marked the denomination’s first formal acknowledgment that racism had played a profound role in both its early and modern history.

By the early 21st century, numbers of ethnically diverse congregations were increasing within the convention. In 2008, almost 20% were estimated to be majority African American, Asian, or Hispanic. The SBC had an estimated one million African-American members. The convention has passed a series of resolutions recommending the inclusion of more black members and appointing more African-American leaders. In the 2012 annual meeting, the Southern Baptist Convention elected Fred Luter Jr. as its first African-American president. He had earned respect by his leadership skills shown in building a large congregation in New Orleans.

By the early 21st century, numbers of ethnically diverse congregations were increasing within the convention. In 2008, almost 20% were estimated to be majority African American, Asian, or Hispanic. The SBC had an estimated one million African-American members. The convention has passed a series of resolutions recommending the inclusion of more black members and appointing more African-American leaders. In the 2012 annual meeting, the Southern Baptist Convention elected Fred Luter Jr. as its first African-American president. He had earned respect by his leadership skills shown in building a large congregation in New Orleans.

The increasingly national scope of the convention has inspired some members to suggest a name change. In 2005, proposals were made at the SBC Annual Meeting to change the name from the regional-sounding Southern Baptist Convention to a more national-sounding “North American Baptist Convention” or “Scriptural Baptist Convention” (to retain the SBC initials). These initial proposals were defeated.

The messengers of the 2012 annual meeting in New Orleans voted to adopt the descriptor “Great Commission Baptists”. The legal name of the convention remains “Southern Baptist Convention”, but churches and convention entities can voluntarily use the descriptor.

Almost a year after the Charleston church shooting, SBC approved Resolution 7 which called upon member churches and families to discontinue the flying of the Confederate flag.

The SBC approved a Resolution 12 titled “On Refugee Ministry”, encouraging member churches and families to welcome refugees coming to the United States. In the same convention, Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission quickly responded to a pastor who asked why a Southern Baptist should support the right of Muslims living in the United States to build mosques. Moore responded, “Sometimes we have to deal with questions that are really complicated… this isn’t one of them.” Moore states that religious freedom must be for all religions.

The SBC approved a Resolution 12 titled “On Refugee Ministry”, encouraging member churches and families to welcome refugees coming to the United States. In the same convention, Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission quickly responded to a pastor who asked why a Southern Baptist should support the right of Muslims living in the United States to build mosques. Moore responded, “Sometimes we have to deal with questions that are really complicated… this isn’t one of them.” Moore states that religious freedom must be for all religions.

The SBC officially denounced the alt-right movement in the 2017 convention. On November 5, 2017, a mass shooting took place at the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs. It was the deadliest shooting to occur in any SBC church in its history and in modern history, an American place of worship.

In a Washington Post story dated September 15, 2020, Greear said some church leaders want to change the name to Great Commission Baptists, to distance the church from its support of slavery and because it is no longer just a Southern church.

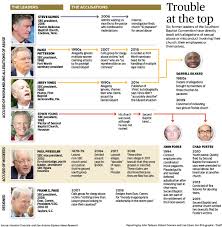

Sex abuse scandal

On February 10, 2019, a joint investigation conducted by the Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio Express found that there had been over 700 victims of sexual abuse from nearly 400 Southern Baptist church leaders, pastors and volunteers over the last 20 years.

In 2018, the Houston Chronicle verified details in hundreds of accounts of abuse. They examined federal and state court databases, prison records and official documents from more than 20 states in addition to researching sex offender registries nationwide.

In 2018, the Houston Chronicle verified details in hundreds of accounts of abuse. They examined federal and state court databases, prison records and official documents from more than 20 states in addition to researching sex offender registries nationwide.

The Houston Chronicle has compiled a list of records and information (current as of June 2019), listing church pastors, leaders, employees and volunteers who have pleaded guilty or were convicted of sex crimes.

On 12 June 2019, during their annual meeting, SBC delegates, who assembled that year in Birmingham, Alabama, approved a resolution condemning sex abuse and establishing a special committee to investigate sex abuse, which will make it easier for SBC churches to be expelled from the Convention. The Rev. J.D. Greear, president of the Southern Baptist Convention and pastor of The Summit Church in Durham, N.C., called the move a “defining moment.” Ronnie Floyd, president of the SBC’s executive committee, echoed Greear’s remarks, describing the vote as “a very, very significant moment in the history of the Southern Baptist Convention.”

I hope that you have really enjoyed this post, you might also be interested in other information which can be found on jmj45tech.com.

Please Leave All Comments in the Comment Box Below ↓

This is a very educational post on the Southern Baptist Convention. The information on the history and background of the Southern Baptist Convention is fascinating, and I didn’t realize it goes back so many centuries.

My sister-in-law and her family belongs to the Southern Baptist Convention and she often refers to them, and especially the motivation she gets from going to church.

So I am very pleased that I could learn more about the Southern Baptist churches and will be sharing this post with the family.

Hello, and thank you for commenting on this article.

I appreciate you considering this article educational, as well as, receiving the information as fascinating.

It is my pleasure that you are pleased.

Have A Blessed Day.

Jerry